Uneconomic trading, market manipulation and baseball

Regulators, including the US Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, are aggressively targeting uneconomic trading in a crackdown on potential market manipulation. Such moves have striking parallels in the history of baseball - some of which might prove instructive for commodity and energy traders, argues Shaun Ledgerwood

Regulators, including the US Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (Ferc), are aggressively pursuing instances of uneconomic trading – the practice of racking up losses in one market in order to benefit positions held in another. But prosecution of this behaviour is relatively new – and some commodity and energy traders are struggling to come to terms with the change of attitude.

Such traders ought to consider baseball. In 1989, Pete Rose was banned from Major League Baseball because he gambled on games while managing and playing for the Cincinnati Reds, including making bets on games his team was playing. Most people innately understand why this practice is forbidden. If a coach or player can bet on a game's outcome, they have an incentive to alter the outcome to benefit their wager. A minor concern with allowing such bets is that they could wager for their team and then take extraordinary efforts to win. This concern is minor, because the bet is consistent with the team's self-interest – and success is constrained by competition provided by the opposing team. A bigger concern is that the coach or player will place bets against their team, then intentionally take actions that cause the team to lose. The competition is then more than happy to assist in the furtherance of the scheme.

So it was with the 1919 ‘Black Sox' scandal, in which eight players from the Chicago White Sox were alleged to have conspired to intentionally lose the World Series to benefit bets made for the opposing team. Public outrage over the incident led to the appointment of the first commissioner for the sport in 1920 and a prohibition on gambling, which led to the banning of eight White Sox players then and, more recently, the banning of Pete Rose.

In effect, baseball recognised almost a century ago that intentional uneconomic behaviour could be used to produce a fraudulent outcome that benefits related positions valued based on that result. By comparison, our regulatory system has only recently begun to prohibit such behaviour in financial and commodity markets.

Concerns of market manipulation currently permeate business headlines. On May 14, the European Commission revealed it was investigating claims that oil and biofuels traders colluded to alter price indexes. In the US, banks and other large energy traders have paid multi-million-dollar fines to settle claims of power market manipulation brought by Ferc over the past two years, while major global banks are also in the spotlight for allegedly manipulating Libor rates. A key common feature of many of these cases is that the trades used to trigger the alleged schemes were designed to lose money on a stand-alone basis, while benefiting related physical or financial positions. As in baseball, a trader seeking to place trades that are profitable on a stand-alone basis will face competition, but a trader who seeks to lose money will face no competition whatsoever in achieving their goal.

Baseball recognised almost a century ago that intentional uneconomic behaviour could be used to produce a fraudulent outcome… [But] our regulatory system has only recently begun to prohibit such behaviour

A relatable example

Part of the problem in understanding how this counterintuitive phenomenon works in financial or commodity markets is getting past the complexity of the instruments involved and the intricacies of the relationships between them. Consider an example based in a market that is more familiar – real estate. Suppose I own an apartment in Washington, DC that is exactly like thousands of other apartments in the area, several hundred of which are currently for sale. The average market price of such an apartment is $500,000, as determined by a web-based price index that is used by everyone in the market and tracks the past 30 days' sales of comparable properties.

Today, there are 19 comparable units in the index, clustered tightly around the $500,000 average price. How much luck would I have if I tried to sell my apartment into the market for $800,000? Likely none, as I have no market power – in other words, no ability to move the price in a direction that favours me on a stand-alone basis. Like a baseball coach attempting to wager on the success of my own team, I cannot raise my price too far above the market, due to competition from other sellers.

Conversely, what if I offered to sell my apartment into this market for $100,000? This offer is uneconomic, as it leaves profits on the table I could presumably obtain if I priced my apartment only slightly below index. Conventional economics would dictate that scores of buyers would beat a path to my door, many offering to bid my price up towards the market average. However, that would ignore my intent. I want to sell my apartment for $100,000 – and not one cent more – to the first bidder willing to take it. Consequently, my act of financial masochism will face no resistance at all. The unit will sell immediately – with me losing $400,000 relative to the market price and the lucky buyer walking away with a $400,000 gain.

Once my intentional uneconomic trade is added to the index, the average market price falls to $480,000. Before discussing my motivations for doing this, consider two consequences of this behaviour. First, every existing apartment owner in the city experiences an unrealised loss of $20,000, potentially impinging their ability to borrow against or profitably sell their homes. Second, I substantially moved the market price with a market share of 5% (one of 20 trades). Basic economics typically views market power as synonymous with larger market shares, which may explain why this phenomenon was ignored for so long by regulators. On the contrary, this example shows no significant market share is needed to execute losing trades that move prices in a particular direction.

Now for my true motivation: after the price drop, I enter the market as a price-taker and buy 50 apartments at $480,000 each, saving a total of $1 million on these purchases and netting a $600,000 profit from the scheme. This is an example of a market manipulation, triggered by a single uneconomic trade executed by a single participant with a 5% market share. The profitability of the scheme depends not on the possession of market power in any traditional sense, but on the ability to leverage gains made from savings on the apartments purchased after the index dropped.

The market disruption caused by this behaviour may be substantial. The anonymous nature of the initial losing trade could elicit similar lowball offers from other sellers panicked by the drop in prices, further biasing the average market price. Because the now-poisoned index is a less reliable mechanism for assessing the true value of apartments, some participants may decide to abandon the index altogether and trade bilaterally to obtain a fairer price. As volume on the index disappears, manipulation becomes more likely, making the index price much less credible as an indicator of the true value of the underlying asset. This possibility explains the need for effective anti-manipulation enforcement as a means to protect the efficiency of price mechanisms over time.

From properties to commodities

Some readers may be sceptical of this example. One could argue that no two apartments are exactly alike, that actual real estate sales are not tied directly to an index, that the purchase of 50 condos would tend to raise purchase prices – and reduce potential gains – and that locking in profits requires that the apartments can be sold later at a higher price.

However, the example becomes more relevant in the context of financial and commodity markets, in which identical units trade based on indexed prices that are often set by a relatively small number of transactions. In addition to leveraging against physical positions that are price-taking to the index, commodity traders can trade derivatives that provide equivalent directional price exposure, with the added benefit of self-liquidation. These attributes underlie why many recent manipulation cases allege the use of relatively small, uneconomic physical commodity trades to manipulate the value of large, leveraged derivatives and index-priced physical positions.

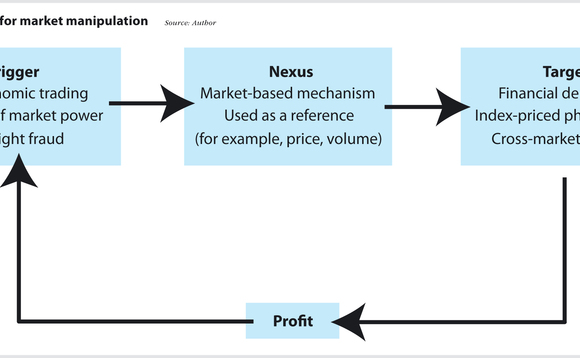

The elements of the example parallel those alleged in many recent manipulation cases concerning the use of uneconomic trading. To understand why, it is helpful to think of a market manipulation as having three components: a trigger, a nexus and a target. The trigger begins the manipulation with an act designed to bias a market outcome, such as a price, causing the manipulation to occur. This biased outcome is the nexus that links the manipulation's cause and effect. This effect alters the worth of the target, which is valued using the nexus and influenced by the trigger. In the real estate example, the initial uneconomic trade is the manipulation's trigger, the index serves as its nexus, and the 50 apartments purchased after the price drop is its target.

This framework describes many of the actual manipulation cases that have been brought by Ferc, which allege that uneconomic price-making trades were used to fraudulently trigger gains in derivatives or physical index targets through the manipulation of an index, auction price or other nexus. The US Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) and Securities and Exchange Commission also bring anti-manipulation cases for uneconomic trading, although these are usually aimed at subcategories of uneconomic behaviour.1 All such cases can be brought under fraud-based anti-manipulation statutes, which specifically ban manipulation triggered by outright fraud, including false statements. Indeed, uneconomic trading can be thought of as a type of transactional fraud, because the trader intentionally inserts false information concerning the commodity's value into the market to trigger their manipulative scheme.

This framework can also explain manipulation triggered by old-fashioned market power. Unlike uneconomic trading, which causes a market to overproduce relative to competitive levels, market power is exercised by an act of withholding that allows the actor to benefit in its primary market on a stand-alone basis. For example, if a seller with monopoly power also holds derivatives that are long the market price, withholding output from the market to generate a price increase simultaneously increases the seller's stand-alone profits in the main market and also increases the profitability of targeted derivatives positions that take that price. As with the example of the baseball coach who bets for their team to win, the ability to trigger a manipulation in this manner is constrained by competitive forces – or, alternatively, by antitrust laws. So while the use of market power to trigger a manipulation is certainly possible, it is easier for a trader to use outright or transactional fraud to trigger manipulation.

The logic of the framework is valuable, because it provides a way to think about different types of manipulative behaviour using a common model of cause and effect. But making broad generalisations about the economics that underlie all manipulations is not appropriate, given the differences in how such schemes can be triggered and executed. This may explain why many economists mischaracterise the problem by inappropriately applying antitrust concepts to what is often a problem of transactional or outright fraud. Unfortunately for the trading community, some of the resulting advice may open traders and their organisations to damages, civil penalties, exclusion from future trading and potential criminal liability.

A few bad apples

Although oddly understudied in economics, schemes that incur intentional losses to produce a greater gain on some ancillary position accompany all competitive activities. Whereas outright fraud is typically prohibited, intentional uneconomic acts usually fall under the radar because losing is dismissed as just part of the game. Notice is finally taken when the behaviour involved is egregious and offensive enough to beg for a response from a regulator. Sports provide great examples of this, from the disqualification of several badminton teams for throwing matches during the 2012 Olympics to the alleged rigging of over 600 European football matches to benefit side-wagers. If the extent of the fraud becomes so widespread or heinous that it shocks the legitimacy of the sport's market – as did the throwing of the 1919 World Series by the Chicago White Sox – the need for more direct intervention to prohibit the behaviour is in order.

It is this kind of response that is currently underway across financial and commodity markets, based on new fraud-based manipulation rules now in place. As the days of the 'Wild West' for trading end, traders must note the historical parallel of how the justice system of the old west often restored order from lawlessness – with the public hangings of several really bad actors, along with a few of their less-guilty associates.2

There is substantial concern that aggressive anti-manipulation enforcement efforts could unwind the strides made towards deregulation of many commodity markets, especially energy. A key fear is that the enforcement of a fraud-based manipulation standard to combat uneconomic trading will create ‘false positives', leading to the wrongful implication of legitimate trades. For example, an attempt to find intentionally uneconomic trades by screening for losses may erroneously identify legitimate trades that happened to lose money. Similarly, efforts to find leveraged manipulation targets could mistakenly implicate legitimate positions that exist only to hedge other trades. Uncertainty concerning errors such as these would unnecessarily reduce liquidity by impeding legitimate trading, making markets easier to manipulate over time.

A slippery-slope fallacy takes this concern to the extreme view that enforcement actions against uneconomic behaviour will create uncertainty sufficient to stifle all cross-market trading, destroy market liquidity by driving away counterparties, and thus work only to the detriment of efficient markets. If it is assumed that manipulation cannot be proven in a logically consistent manner, the conclusion is either that enforcement should refrain from pursuing such cases at all, or that the burden of proof for establishing liability should be so stringent that effectively no-one can ever be found guilty of manipulation. Proponents of this outcome wrongly assume the discussion over whether uneconomic trading and other types of fraud-based manipulative behaviour should be curbed is just beginning. In fact, this debate has already run its course through the political process, and the trading community must adjust accordingly.

The issue is no longer whether uneconomic trading is prosecutable, but rather how broadly the existing anti-manipulation efforts should extend. This could conceivably range from the current case-by-case analysis of potentially manipulative behaviour to a draconian ban on traders participating in markets in which prices are set if they hold positions that are valued based on those prices.

Such a step seems disproportionate – a reaction some would argue is similar to the ban handed down to Pete Rose, who in 2007 admitted to the seemingly innocuous crime of betting on the success of his own team. To mete out automated punishment on traders who lose money in a physical market and then benefit from another position would effectively eliminate hedging and other legitimate trading practices, defeating the purpose for which financial markets were created in the first place. An outright ban is also inconsistent with manipulation laws, which require proof of fraudulent intent.

It is more reasonable to observe that a presumption of legitimacy must be attached to all open market trades. The framework discussed above is useful in testing this presumption. Behaviour that is not intentionally uneconomic, fraudulent, or a result of the exercise of market power is legitimate and cannot serve as a manipulation trigger. If this test is failed, the next question is whether the trader held other positions with sufficient financial leverage to make the manipulation profitable overall. Finally, if leverage exists, the strength of the nexus must be shown to demonstrate the causal linkage between the trigger and target. If this third element is proven, the burden shifts to the trader to prove they were not manipulating the market. This is equivalent to the process already used by regulatory agencies in the US, including Ferc, which evaluate manipulations on a case-by-case basis.

Insider trading

The goal of this article is to further compliance, which necessarily requires acknowledgement that current anti-manipulation enforcement efforts are a permanent fixture in commodity markets. Nevertheless, some market participants continue to oppose that suggestion. They should remember that 30 years ago, insider trading was generally not prosecuted in the US, due largely to the meaningless penalties attached. That changed with signing of the Insider Trading Sanctions Act of 1984, which gave US regulators substantial new civil and criminal penalties to deter the behaviour. Conservative pundits at the time argued the new prohibitions were not provable in a court of law – and that if they were provable, then the bar for liability should be set so high that nobody could possibly be found guilty, as the successful application of the new penalties would otherwise chill all legitimate trading.

Late last year, the most conservative members of Congress not only embraced those rules, but championed the passage of the Stop Trading on Congressional Knowledge Act to extend them to their own membership. Likewise, years from now, the illegality of intentional uneconomic trading in financial and commodity markets will be settled. Traders and their organisations must therefore be proactive in recognising the world has changed. As compliance officers adjust to rules that favour self-reporting violations, traders will increasingly find themselves exposed and liable for disgorged profits, civil penalties up to $1 million per incident, per day, and potential criminal charges. Those convicted may also find themselves banned from trading for life - an outcome for which no-one wishes to come out smelling like a Rose.

1. An example is ‘banging the close’, which involves selling large, uneconomic volumes in the final moments of the trading day to lower mark-to-market prices.

2. For example, in the wake of the Black Sox scandal, ‘Shoeless’ Joe Jackson suffered a lifelong ban from baseball despite lack of proof of any direct wrongdoing.

Shaun Ledgerwood is a senior consultant at The Brattle Group in Washington, DC, and a former economist in Ferc's enforcement division.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@risk.net or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.risk.net/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

More on Regulation

EU trade repository matching disrupted by Emir overhaul

Some say problem affecting derivatives reporting has been resolved, but others find it persists

Barclays and HSBC opt for FRTB IMA

However, UK pair unlikely to chase approval in time for Basel III go-live in January 2026

Foreign banks want level playing field in US Basel III redraft

IHCs say capital charges for op risk and inter-affiliate trades out of line with US-based peers

CFTC’s Mersinger wants new rules for vertical silos

Republican commissioner shares Democrats’ concerns about combined FCMs and clearing houses

Adapting FRTB strategies across Apac markets

As Apac banks face FRTB deadlines, MSCI explores the insights from early adopters that can help them align with requirements

Republican SEC may focus on fixed income – Peirce

Commissioner also wants a revival of finders’ exemption, more guidance for UST clearing

Streamlining shareholding disclosure compliance

Shareholding disclosure compliance is increasingly complex due to a global patchwork of regulations and the challenge of managing vast amounts of data

Banks take aim at Gruenberg’s brokered deposit rule

Regulatory lawyers question need to reverse 2020 rulemaking just four years later