Pension funds weary of interest rates high-wire act

Rising rates would help reduce pension fund deficits, but would also hurt the sector’s hedges. That could be managed by trimming hedge ratios, but funds are scared of acting too soon. By Cecile Sourbes

The announcement was made in Washington, DC; the groans of disappointment came from Hellerup in Denmark, among other places.

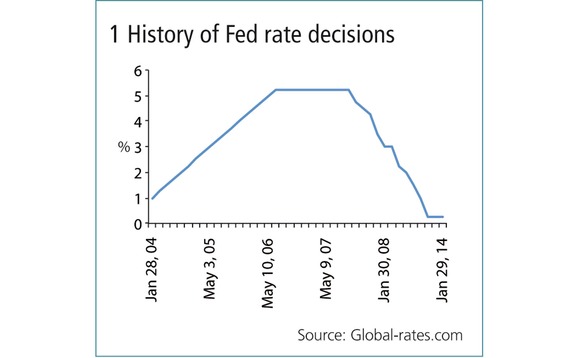

It was January 29, and the Federal Reserve Board’s rate-setting committee had just dashed hopes that the winding down of its bond-buying programme would be swiftly followed by the central bank’s first rate hikes in eight years. For pension funds, which have seen the value of their liabilities balloon as rates have fallen, it was the latest postponement of what would be a very welcome reprieve – and a further reminder that the future path of interest rates is not as clear as it might initially seem.

“We were disappointed by what happened in the US in January,” says Henrik Olejasz Larsen, Hellerup-based chief investment officer (CIO) of Danish pension fund, Sampension, which would see the size of its liabilities shrink by €20 million for every 1 basis point rise in rates. “We still do expect interest rates to rise this year. [But] it’s not unrealistic to think rates could also stay low for a long period of time,” he adds.

And that, in a nutshell, is the problem. If rates rise, fund liabilities will fall, relieving some of the pressure on CIOs such as Larsen. But the bond and swap portfolios that are used to hedge funds’ interest rate exposure will simultaneously lose value. The obvious solution is to trim those hedges, but what if rates do not rise? What if they rise and then dip again?

“Pension funds seem to have a common understanding rates will go up at some point, so they are all eager to terminate their hedges. The problem is that if they terminate them too soon, their solvency ratio will take a hit because rates can go lower. The worst-case scenario might be that rates go up just a little bit, prompting some of the largest pension companies to cut their hedge ratios very rapidly, and then rates go back down,” says one Copenhagen-based head of risk advisory at a Nordic bank.

We still do expect interest rates to rise this year. [But] it’s not unrealistic to think rates could also stay low for a long period of time

A number of funds are said to have made this mistake already, paring back hedges over the past couple of years, when it seemed rates must rise, only to be left uncovered when they did not.

A lot rides on these decisions. A study published in September 2013 by the Dutch central bank revealed 414 domestic pension funds – which had hedged some 48% of their interest rate risk at the end of December 2012, using primarily sovereign bonds and swaps – would see the total value of their liabilities fall by €155 billion in the event of a 1 percentage point increase in interest rates. It also showed the market value of their bonds and interest rate swaps would fall by €16 billion and €33 billion, respectively.

Despite the continuing freeze on central bank hikes, market rates have risen over the past year – but not very much – and remain sensitive to the first sign of trouble anywhere else. At the end of April 2013, the 10-year US Treasury bond was yielding around 1.67% according to data from Bloomberg – as of April 28 this year, it was just over a percentage point higher, at 2.70%. But most of that rise happened during a frenetic fixed-income sell-off in May, June and July last year. For 2014 to date, yields are down.

So what is likely to happen next? Market participants are divided. “While base rates are anchoring the short end of the curve, yields at the long end are influenced more heavily by supply and demand. The question pension schemes should ask themselves is not whether yields are likely to rise – markets are already pricing in yield rises – but whether yields will rise more quickly than the market expects. From my perspective, there is some value to be had currently in being strategically under-hedged,” says Andrew Stephens, managing director within the institutional business at BlackRock in London.

Robert Gall, head of market strategy within the financial solutions group at Insight Investment in London, is comfortable with the market’s consensus. “If we look at forward rates to see how the yield curve is priced, the market has already built in an expectation that rates will rise in the future and could reach around 3% in five years’ time and maybe 4% in 10 years, but I don’t expect them to rise faster than that,” he says.

For schemes with a low hedging ratio, any rise would be unambiguously good. The Universities Superannuation Scheme (USS) in the UK, for instance, has approximately 25% of its fund invested in nominal and inflation-linked bonds. “Given the modest rise in rates expected, there would be limited impact on the asset side. Rising yields, however, reduces the valuation of our liabilities, providing some relief from historically low rates, particularly inflation-linked yields, which have raised the discounted value of our liabilities in recent years,” says Roger Gray, CIO of USS in London.

Although the yield for 10-year gilts has gone up significantly since June last year – jumping from 2.14% on June 18 to 3.07% on December 27 on the back of an improving economic outlook for the UK – their level remains relatively low, according to Gray, which has resulted in USS reporting a deficit for each of the past three years. “The possibility of interest rates remaining low over a long period of time, or asset markets weakening after the support from quantitative easing wanes, could have a significant impact on the long-term funding of the scheme,” says Gray.

For funds that do have a portfolio of hedges to protect, one response used in the UK is to put in place a swaptions-based overlay. Over the past couple of years, funds have explored the use of swaptions for a variety of reasons – boosting yield by selling relatively high-strike payers, adding protection against further falls in rates, putting in place collared positions that sacrifice some of the liability reductions in a rising-rates environment for downside safety, or seeking to offset hedging losses if rates rise.

In theory, selling a receiver swaption is one way to benefit from a near-term increase in rates – if interest rates fall, the buyer would exercise and the fund would be stuck in a swap that required it to pay above-market fixed rates. This would erode the low-rate protection offered by the fund’s existing swaps. But if rates remained steady or rose, the fund would continue collecting premium until the trade’s expiry, helping to offset losses in the hedge portfolio. Buying a payer swaption would have a bigger upside, dealers say, but without the premium income.

“Swaptions have been a big talking point over the past 18 months or so among pension funds in the UK, and we’ve used a variety of approaches. A pension fund would typically buy a receiver or sell a payer swaption. But some schemes have decided to buy payers as well as receivers, while some others have sold receivers. So pension funds can actually incorporate swaptions into their liability-driven investing strategy in all manner of ways,” says Gall.

Selling swaptions can have the added benefit of generating a stream of premium income but Gall says the strategy has become a victim of its own success, with pension fund supply serving to compress the available premium. According to research published by Russell Investments in June 2011, a pension fund that sold a three-year option on a 10-year swap could earn more than 400 basis points. Today, the same trade would net around 200bp, one asset manager says.

“Given the way the volatility has moved, prices have gone lower recently. But because these schemes are so big, even if they get paid a fraction, a swaption on a large amount can result in a decent income,” says Gall.

But swaptions strategies have their own complications, says Thomas Ellerton, a London-based vice-president in rates structuring and solutions at Citi. Where the swaptions are being used to supplement existing hedges, there is no natural offset for their mark-to-market gains and losses, generating mark-to-market volatility.

“When pension funds buy these options they must be aware of the P&L volatility they can have on their book. Some would think that when interest rates rise, volatility would come up as well, so they want to have that exposure, but others have realised from past experiences that they have introduced P&L volatility that wasn’t there before – they don’t necessarily have the offsetting mark-to-market risk on the liabilities side. It needs to be closely managed,” he says.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@risk.net or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.risk.net/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

More on Interest rate markets

New benchmark to give Philippine peso swaps a fillip, post-Isda add

Isda to include new PHP overnight rate and Indonesia’s Indonia in its next definitions update

SABR convexity adjustment for an arithmetic average RFR swap

A model-independent convexity adjustment for interest rate swaps is introduced

NatWest Securities US Treasury trading head departs

Jason Sable joined the UK bank in January 2022 from BNP Paribas

CME in talks to clear term SOFR basis swaps

US clearing house has held discussions with some dealers about clearing term SOFR-SOFR packages

Risky caplet pricing with backward-looking rates

The Hull-White model for short rates is extended to include compounded rates and credit risk

The curious case of backward short rates

A discretisation approach for both backward- and forward-looking interest rate derivatives is proposed

Cross-currency swaps will use RFRs on both legs, says JP exec

Despite slow start, all-RFR swaps will become the market standard within a year, according to Tom Prickett

June mid-month auctions – Coupon and yield trends

As Treasury issuance amounts set new records, coupons at the front end of the curve have marched downward, while back-end coupons have lagged. Yield spreads across each popular measure show a consistent steepening of the curve through the first half of…